System thinking for designers

Author

Willem Duijvelshoff

Published

01 March 2018

Reading time

3 minutes

Systems are everywhere. Whether you look at organizations, societies or information technology. Everything you see is essentially part of a greater entity, in other words, part of a system. Systems are characterized by relationships and dependencies and are constantly changing. What can designers learn from this way of looking?

System thinking

A system is a set of related components that work together in a particular environment to perform whatever functions are required to achieve the system’s objective

Donella Meadows

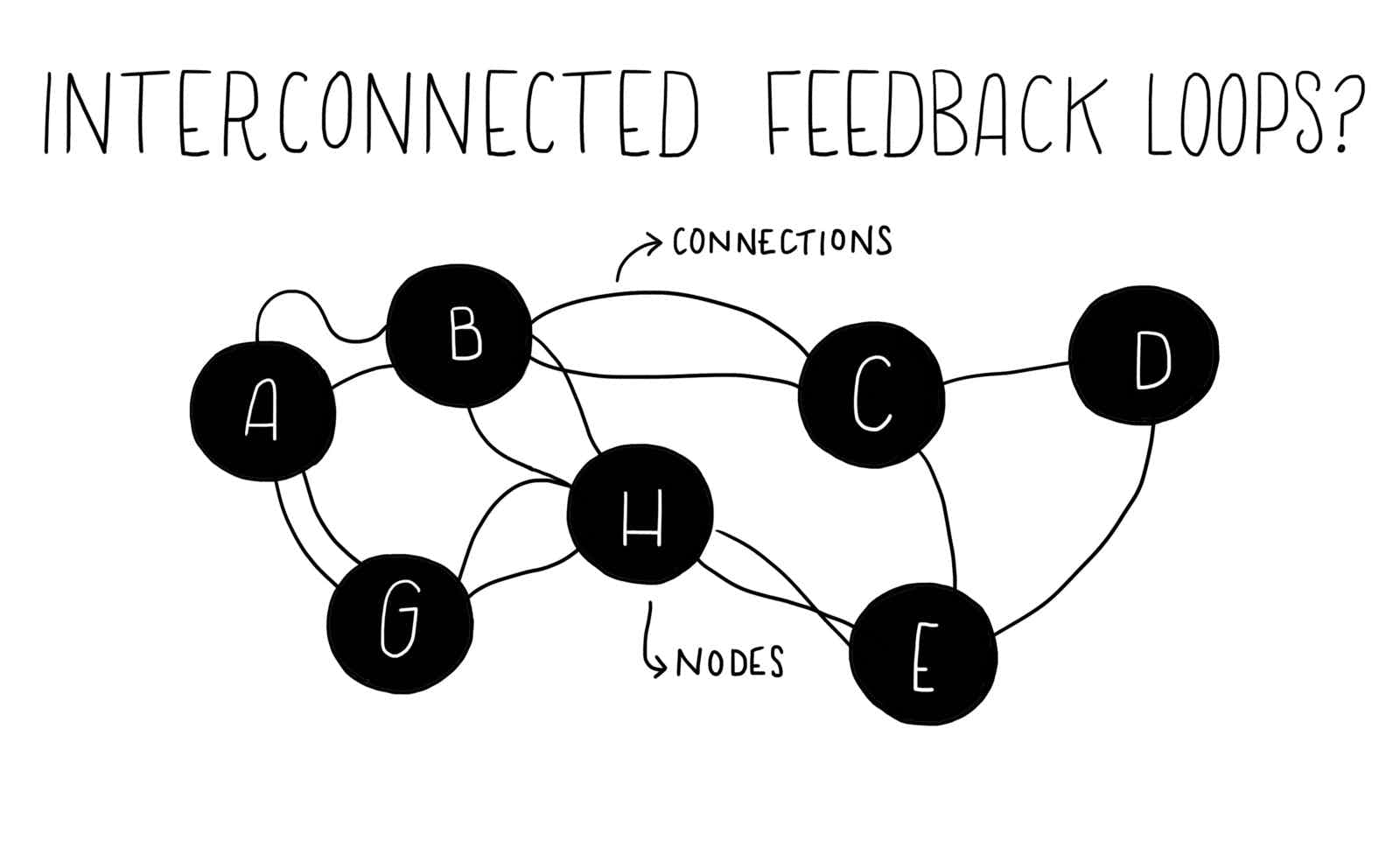

To create order in thinking about complex problems, systems thinking has been created, a theoretical view that helps to map the bigger picture. Through this perspective, problems or inconsistencies can be identified, and a shared understanding of a design problem can be achieved. For designers, this especially helps to give insight into all elements in a system, before diving into visual design.

Hugh Dubberly and Paul Pangaro speak of 'systems literacy' as a new quality that designers must possess in a networked society. Systems thinking is relevant for designers because, ideally, they not only look at the design of the individual items ('screens'), but also from a zoomed-out point of view as well as from within the context of the user. Theories and tools of systems thinking too, can be useful for understanding organizations in which you are active as a designer. By mapping out how information is exchanged and which stakeholders influence the design process.

How does systems thinking work in practice?

A project by Invorm – aimed at a redesign of a waste processing aid – provides insight in how systems thinking can work in practice. Various types of roles, like planners, work planners and drivers, make use this resource. The roles use different modules within the system and continuously exchange information.

Work planners draw waste areas on a map, planners look at these areas daily and link vehicles to routes. The drivers see the routes on their navigation. If the driver has feedback or identifies errors in the route, this can be communicated via the application, after which planners and work planners can integrate the feedback again in the routes and in the planning.

Once the roles have been roughly mapped, and different modules within the system and how information is exchanged via possible feedback loops have been made visible, the system can be improved and refined.

As next step you determine the most essential parts of the system and leave out the parts that do not add value. The overview can also be used to determine whether a functionality is in a logical place. This way, as a designer, you can move around with modules and cluster them in a logical way.

In addition, the overview helps to visualize whether certain components can be reused. If certain information is requested during onboarding, the same pattern can be used if this information is adjusted in settings, increasing the consistency of the system.

In conclusion

Maintaining an overview through systems thinking can prevent diving into the details too quickly. This way you ensure that no designs are made that later turn out to be unrelated to the bigger picture. A visualization aligns the team and other stakeholders and helps to give direction to a product and the overarching strategy. In addition, design remains a circular process. In the context of systems thinking, this means that a system continues to evolve and is never 'finished'.

Consulted sources

- Applying systems thinking in product design (Shekman Tang)

- Tools of a system thinker (Leyla Acaroglu)

- Integrating systems thinking and design thinking (John Pourdehnad, Erica R. Wexler en Dennis V. Wilson)

- Design thinking needs to think bigger (Steve Vassallo)

- Cybernetics and design: Conversations for action (Hugh Dubberly en Paul Pangaro)